In the House of Paul-Émile Borduas

Exploring Borduas' Art

Influences

Paul-Émile Borduas, Joust in the Apache Rainbow, 1949,

(lateral detail), oil on canvas.

Collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

Photo Luc Bouvrette.

© Paul-Émile Borduas Estate / SODRAC (2013)

Borduas’ work was strongly marked by a number of influences – his early upbringing, his first trip to France and his contact with Modern European and American painting are some that come to mind. However, more than anything else, his work had three major influences: Ozias Leduc; André Breton and the Surrealists; and the young artists who would form the Automatist group.

To begin with, Borduas’ profound respect for Ozias Leduc, nicknamed the “sage,” shaped his view of painting and life in general. Leduc gave Borduas his first art lessons and introduced him to religious painting and art history. The master’s paintings in the Saint-Hilaire church where Borduas went to mass with his family as a child gave him his first contact with works of art. Leduc became his mentor and assisted him both financially and intellectually for long periods. By taking Borduas as an apprentice, encouraging him to take courses at the Montreal school of fine arts and giving him the chance to go to France to study religious art, Leduc enabled the young artist to fulfil his talent and follow his own path. Borduas remained grateful, even in his most difficult periods. Leduc was the pillar that he could always rely on and confide in.

Joust in the Apache Rainbow,

François-Marc Gagnon

Video clip

Duration: 1 minute 34 seconds

Download the video file (8 MB)

Transcript | Download the QuickTime plugin

In his text Projections libérantes (Liberating projections), Borduas related that on October 10, 1928, he wrote to the principal of the school where he was teaching to hand in his resignation:

« When the letter was written, I went to find my dear Monsieur Leduc. His fine intelligence – his full approval of this irreparably rash gesture – was more precious than everything I had just deliberately lost. »

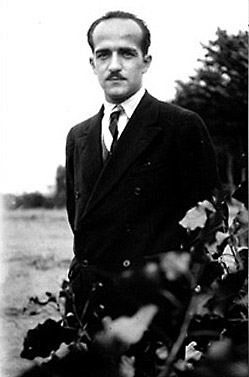

Paul-Émile Borduas, around 1932

Paul-Émile Borduas archives

of the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal.

Photo : MACM

The influence of André Breton and Surrealism was very different, since it was not part of Borduas’ everyday life and surroundings. Borduas never met Breton in person and he discovered the views of this Surrealist through his writings alone. Nevertheless, in Surrealism Borduas found theoretical affiliations and intentions that corresponded to his own vision of art.

Finally, the influence of the young Montréal artists, while less tangible, was central to the expression and fulfilment of Borduas’ vision. The group’s discussions, as well as its energy and exhilaration, were instrumental in developing his thought and giving it coherence. The ideas, contacts and actions of each artist provided material for theorization and helped to define the Automatist movement. Although the influence of these young artists is often ignored, its effect on Borduas’ life and artistic production was comparable to that of Ozias Leduc. For example, Borduas wrote about La Chasse-galerie (The Flying Canoe), ca. 1946, a painting by Mousseau, in these terms:

« If I like the «Chasse-galerie», it cannot be for its evocation of a squall. For me a squall is beautiful and interests me only when it’s in the sky. Mousseau’s squall can give me only a ridiculously diminished idea of one, because of its immobility, if nothing else. No, if I like this painting it’s because it is as unique and inimitable as he is, with its own enticing reality. If I had never seen it, I would not be exactly what I am. »

Borduas’ affection and recognition of these young artists was real and tangible. He accepted and respected these young people’s ideas and vision. Their influence continued to affect him long after he had left for New York and Paris. His correspondence with group members like Claude Gauvreau was full of intellectual and theoretical exchanges.

Header image: Borduas in his Saint-Hilaire house with Gabrielle, and Renée (1950). Collection Gilles Lapointe collection.

VIDEO TRANSCRIPT

Joust in the Apache Rainbow

François-Marc Gagnon

The first thing that must be understood about Borduas, is how he arrived at Automatism. This painting, Joute dans l’arc-en-ciel apache (Joust in the Apache Rainbow), dates from about 1947, so it appeared a little later. Already in 1942, Borduas had read a text by André Breton containing a passage about Leonardo da Vinci that intrigued him. Breton quotes the advice given by Leonardo to his pupils: “Find an old wall, stare at it for a long time and shapes will appear; you just have to copy these shapes and your inspiration will be renewed.” This is the key to many Automatist paintings. Not that Borduas literally went out to stare at an old wall, but he considered the sheet of paper or the canvas like a wall on which he drew a line, any kind of line, and then a second line, a third one, and this added-up and produced .... a rainbow, as in this painting. His Automatist paintings all have precise titles, not just “Painting” or “Untitled” because little by little, an image appeared and the interpretation Borduas made of it became the name of the painting.

In an article entitled “Quelques pensées sur l’oeuvre d’amour et de rêve de M. Ozias Leduc” (Some thoughts on the work of love and dream of M. Ozias Leduc), Borduas wrote about the influence of this artist and that of André Breton:

« I owe [Leduc] a love of beautifully executed painting that was awoken even before I met him. I owe him one of the rare permissions I have had to pursue my destiny. When it became evident that I was putting my faith in values that were contrary to his hopes, no opposition, no resistance, was brought to bear; his precious and constant sympathy was not altered. That alone was enough to earn M. Leduc a unique place in my admiring gratitude, to place him in a more perfect world than the everyday one.

I owe him – and this is something one keeps on acquiring, but never perfectly – a love of careful work, while to Breton I owe a love of risk that will always stay with me. Yet there is much risk in Leduc’s work. It is hidden, however, in an apparent steadiness that makes it difficult to see, and without Breton I might have discovered it only partially.

Finally, I owe him the permission to go from the spiritual and pictorial atmosphere of the Renaissance to the power of dream, which opens the way to the future. »

In the text “En regard du surréalisme actuel” (Concerning today’s Surrealism), Borduas concluded with these words: « Breton alone remains incorruptible ».

In “Le surréalisme et nous” (Surrealism and ourselves), he wrote:

« Surrealism was for us the occasion when our senses evolved. It made possible the burning contact with generous scandals that we probably would not have known without it, bogged down as we were in countless prejudices.

Surrealism put the work of art back into the world of human activity. It provided a better understanding of poetic creation. It revealed to us the continuation of the prophecies.

Surrealism was for us a magnificent example of courage, of ardour. Surrealism, through every aspect of its behaviour, revealed a large part of who we were.

We are the unforeseen sons, indeed the almost unknown sons, of Surrealism. Illegitimate sons, perhaps, whose filiation occurred at a distance, not voluntarily on our part, but by force of circumstance. »

Borduas’ own relationship with Surrealism remained ambiguous. On the one hand, he found it important in developing the Refus global manifesto. On the other hand, he was disappointed that European members of the Surrealist movement had distanced themselves from a precept he considered fundamental, that of the non-preconceived act.

© Musée des beaux-arts de Mont-Saint-Hilaire, 2014.

All rights reserved.