In the House of Paul-Émile Borduas

A Global Refusal

Genesis

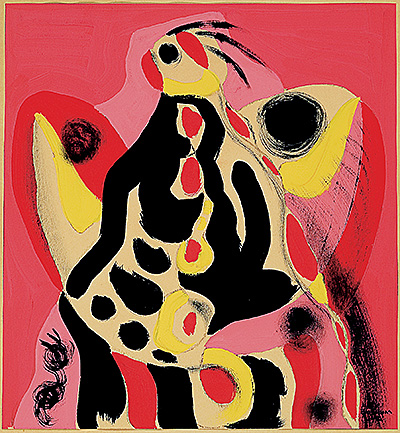

Paul-Émile Borduas, Untitled (One Bird), 1942, gouache,

charcoal underdrawing.

Collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts,

gift of Mr. Denis Noiseux and Mrs. Magdeleine Desroches‑Noiseux.

Photo MMFA, Christine Guest.

© Paul-Émile Borduas Estate / SODRAC (2013) In the post-war period of the late 1940s and under the government of Premier Maurice Duplessis, Québec was an inward-turning society dominated by the clergy. Borduas and his friends wanted to see a profound change in Québec mentalities. For them, producing the text known as Refus global (variously translated as Total Refusal, Global Refusal or Global Rejection) was a first step toward this goal, since it questioned the authority of the Church and defined the Québécois as a subjugated people. The manifesto denounced social injustices and called for the creation of a new culture based on the senses rather than reason and on liberty rather than obedience: « We foresee a future in which man is freed from useless chains, to realize a plenitude of individual gifts, in necessary unpredictability, spontaneous and resplendent anarchy. Until then, without surrender or rest, in community of feeling with those who thirst for better life, without fear of set-backs, in encouragement or persecution, we shall pursue in joy our overwhelming need for liberation.»

Signed by 16 members of the Automatist group, the Refus global manifesto was far ahead of its time – it came too soon and too brusquely. In 1948, Québec society and its authorities were in no way ready to hear and understand the demands of this group of artists. Fear of the Other and the unknown would not dissipate until the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s, when rapid developments in Québec society wrought major changes.

When Borduas returned from Europe in 1930, the economy was still reeling from the effects of the Great Depression and he had difficulty finding contracts. He worked with Ozias Leduc and managed to obtain a few small projects doing religious art, such as painting the Stations of the Cross for the Saint-Michel-de-Rougemont Church. Sadly, most of his attempts to find work with churches were unsuccessful. Projects were either entrusted to another artist or simply cancelled due to insufficient funds. Borduas was disappointed and somewhat bitter about this lack of interest in his art. The need to support himself and his growing family led him to return to teaching.

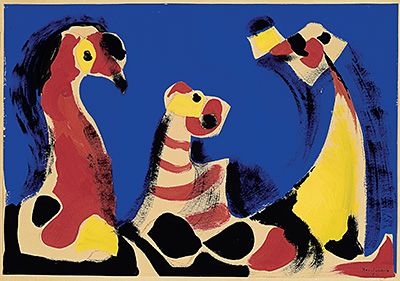

Paul-Émile Borduas, Untitled (The Three Pointed Forms, 1942,

gouache, charcoal underdrawing.

Collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts,

gift of Mr. Denis Noiseux and Mrs. Magdeleine Desroches‑Noiseux.

Photo MMFA, Christine Guest

© Paul-Émile Borduas Estate / SODRAC (2013)

From 1933 to 1939, he gave drawing lessons to children in Montréal schools. In 1937, he was hired by the École du meuble as a drawing and decoration professor. He also organized drawing classes for children in his Montréal home in 1941. The children’s liberty of expression enchanted him and was a factor in his still embryonic conception of a freer vision of artistic creation. He wanted to integrate this impulsive and primal approach into the way he taught children and into his own practice as well. He felt an ever-growing frustration with the academic restrictions imposed by teaching institutions. As he got to know a group of young people in his circle who looked up to him as a mentor, he felt obliged to question accepted artistic practice and society in Québec. Intense discussions with these young people encouraged him to develop new ideas. His experience with children and young people, along with his dissatisfaction with the omnipresence of academism and religion, led him to reflect on society in general. Everywhere, he found himself confronted by barriers and rules that were both imposed and imposing. In this period, he also discovered European non-figurative Modern painting and became acquainted the Surrealists’ manifesto; this opened up vistas of new, liberating way of doing art, very close to his own vision of things.

The genesis of Borduas’ new way of thinking can be sensed in his artistic production from around 1942, when he took the first steps in his exploration of non-figurative painting; the Refus global of 1948 represents the culmination of this thought. A series of gouaches (1942-1943) is evidence that Borduas was experimenting and developing techniques in a way that typified the Modern spirit that now possessed him. Little by little, the route to be taken became clear in his mind. The Refus global manifesto was taking shape. One new idea engendered another. The vision of a better world and a liberation of the spirit began to gradually appear in his work. The first fruit of this thinking is also found in articles Borduas wrote and published at this time, such as “Fusain” (Charcoal) (1942) and “Manières de goûter une oeuvre d’art” (Ways of savouring a work of art), (1943), which had been previously presented as a lecture before the Société d’étude et de conférences on November 10, 1942. These texts give some idea of what Refus global would focus on.

Header image: Inverted detail of a page from the Refus global manifesto.

A passage from Projections libérantes (Liberating projections):

«Children, whom I now never lose sight of, open wide the door to surrealism and automatic writing for me. The most perfect condition for painting has at last been revealed to me. I had made peace with my first feeling about art, which I expressed something like this: “art, an inexhaustible spring that flows unimpeded from man.” The confusion of this child’s definition, which I nevertheless retrieve for its opposition to any idea of impediment when it comes to creative work, gives sentimental expression to the need for abundant exteriorization. In the noble hope of making me a slave like everyone else, and with my trustful acquiescence, people scuttled this. After being shipwrecked and submerged for a long period, this primordial need rose to the surface. My behaviour was thus modified: it enables me to have a new contact full of faith in the society of half-liberated men and women – a society whose existence I hadn’t even suspected in Montréal.»

Passage from the text “Ce destin, fatalement s’accomplira” (This destiny inevitably will come to pass), written by Borduas in 1943:

«Encouraged by stunning discoveries of a psychological nature, the artistic disciplines could envision an immense field of experimentation and possible victories – that of the subconscious; new paths began to open up, giving rise to very different styles. Some sought mystery in the suggestiveness produced by associating unexpected, strange and disconcerting elements in a painting, in order to intensify the impression through a rendering that tested the limits of illusion and credibility. Others looked for it in the directions given by Leonardo da Vinci to his pupils. Salvador Dali stood out, trying out these possibilities.

Still others turned to decalcomania, in thousands of experiments, ensuring randomness. Others started with automatic writing and went on to automatic painting, and the stage we are at now.»

© Musée des beaux-arts de Mont-Saint-Hilaire, 2014.

All rights reserved.