In the House of Paul-Émile Borduas

Exploring Borduas' Art

Evolution of His Creative Gesture

Paul-Émile Borduas, Stations of the Cross, 1931-1932.

«The Meeting» (left),

«The Entombment» (right).

Collection of the Société du patrimoine religieux du

diocèse de Saint-Hyacinthe.

Photo: Luc Bouvrette.

© Paul-Émile Borduas Estate / SODRAC (2013)

After returning from France in 1930, Borduas obtained a few small contracts for religious paintings, but the effects of the Great Depression made it difficult to find work. To support himself and eventually his growing family, he went back to teaching. Contact with children and their spontaneity gradually had a transformative influence on his painting. This development drew attention at the 1940 Salon du livre canadien (Canadian book fair), in which Borduas exhibited his work, described by a journalist as “a landscape painted without any concern for convention, in voluptuous colours rarely seen here.” Stylistically, Borduas’ work began to evolve from the static classicism of his Stations of the Cross in the Rougemont church to a freer expression of his artistry. During his stay in France, he had discovered the work of certain European artists like Cézanne, Renoir, Matisse, Picasso and Maurice Denis, and this had broadened his horizons and enriched his artistic approach.

In the spring of 1942, Paul-Émile Borduas exhibited a series of 45 gouaches at the Foyer de l’Ermitage in Montréal. These paintings revealed the first signs of Borduas applying the notion that a work of art could be created without preconceived ideas. In this series, Borduas explored personal and non-preconceived expression, transposing the concept of “automatic writing,” as defined by the Surrealist André Breton (1896-1966) to pictorial creation, while still retaining figurative traces of form, colour and movement. Borduas’ interest in gesture and the harmony of colours derived from his great admiration for Cézanne and Renoir, two painters little esteemed by the Surrealists, who did not share such concern for plasticity. It was during this time that young artists, many of whom were students at the École du meuble, began to frequent Borduas’ studio. This group of young people were strongly influenced by Borduas’ vision and saw him as their master; he thus became the leader of the Automatist movement.

In quest of the subconscious, the Automatist artists believed in seeking pictorial expression based on the primal gesture, the accidental and the purity of the present moment. These artists’ work began to echo the same liberty of expression as that found in the “automatic writing” inspired by André Breton’s Surrealist texts. With time and having gained attention through a few exhibitions, the Automatist movement became a force to be reckoned with, capable of breaking through the frontiers of traditional Québec art. The group’s multidisciplinary nature was a source of enrichment for the members and led them to explore the interaction between such disciplines as dance, photography, literature, painting and sculpture. This approach corresponded closely to the ideas Borduas developed in the Refus global manifesto (variably translated as Total Refusal, Global Refusal and Global Rejection).

The years preceding the publication of Refus global were intense, representing a decisive period in the lives of all the members of the group. For Borduas, it was a time when his pictorial production underwent a transformation and, at the same time, his vision and creative thought shifted, changed shape and crystallized.

On July 22, 1947, he wrote to Fernand Leduc:

«More and more, I distinguish two activities: that of the Dream, the best, the ideal, the Perfect, for which the impossible may be the rule. This activity tolerates no dishonest compromise. The other, strictly practical, is that of commerce, communication and trade, for which doing one’s best seems to be the ideal rule.»

Borduas felt that artistic production should be separate from the real world, with its structures and strictures. Creation should be pure, spontaneous and free. After the publication of the manifesto, the social and personal backlash was such that by 1948 the group was becoming less cohesive. In an exhibition entitled “La matière chante” (Matter Sings) held at the Galerie Antoine in 1954, there were signs that the Automatist movement was coming to an end. It was, however, far from the end of Borduas’ creativity. In 1953, he moved to the U.S.A. and settled in New York. There he discovered an artistic vision compatible with his own, as well as the work of American Abstract Expressionists, like Jackson Pollock (1912-1956) and Action Painting.

In 1955, Borduas left New York for Paris. Colour virtually disappeared from his work. Black and white filled every inch of his canvasses. His painting never ceased to evolve.

Header image: Paul-Émile Borduas, around 1932 (detail), Paul-Émile Borduas archives of the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal. Photo : MACM

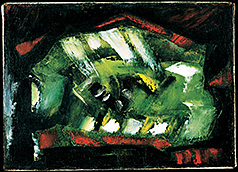

Paul-Émile Borduas, Green Abstraction, 1941, oil on canvas. Collection of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, purchase, grant from the Government of Canada under the terms of the Cultural Property Export and Import Act, and Harry W. Thorpe. Photo MMFA, Brian Merrett.

© Paul-Émile Borduas Estate / SODRAC (2013)

This painting is considered to be Borduas’ first abstract work of art. He said that he himself had destroyed many of his own paintings over his career, because he was not satisfied with the results:

«In Father Corbeil’s first exhibition, in Joliette in 1941 or 1942, there was Harpe brune (Brown Harp), a preconceived abstract painting preoccupied with geometry and expressionism. The internal duality of this painting led me to destroy it one day, despite its national success as a curiosity. All that remains of it is a photograph and a few favourable reviews. The second work was a horrible head rising vertically on a horizontal background done in impasto, suggesting a beach. I don’t know why I entitled this painting «Le Philosophe» (The Philosopher). Nothing remains of it. Finally, a third painting, «Abstraction verte» (Green Abstraction), dated 1941, stayed modestly but firmly on the wall. Of the three, it was the only painting to find favour in my destructive rage. It is the first entirely non-preconceived painting and a harbinger of the Automatist storm clouds already gathering on the horizon.»

© Musée des beaux-arts de Mont-Saint-Hilaire, 2014.

All rights reserved.