In the House of Paul-Émile Borduas

Exploring Borduas' Art

Artistic Approach

Paul-Émile Borduas, Floraison massive, 1951,

oil on canvas.

Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario,

Gift from the Albert H. Robson Memorial Subscription Fund.

Photo AGO.

© Paul-Émile Borduas Estate / SODRAC (2013)

« Is not the art of painting the mute art par excellence? »

These few words of Borduas’ say a great deal about what he thought of art in general. He considered painting to be an art that was not understood verbally, but rather experienced in feelings. Words seemed to him unsuited to expressing the source of inspiration, the process of expression or the effect of the result. For Borduas, the gesture of painting was a primal, impulsive and subconscious act. The spontaneity of children’s drawing was a convincing example of this: «Children, whom I now never lose sight of, open wide the door to Surrealism and automatic writing for me. The most perfect condition for painting has at last been revealed to me. I had made peace with my first feeling about art, which I expressed something like this: “art, an inexhaustible spring that flows unimpeded from man.” The confusion of this child’s definition, which I nevertheless retrieve for its opposition to any idea of impediment when it comes to creative work, gives sentimental expression to the need for abundant exteriorization. »

The art of painting was the expression of a feeling, or an emotion, without any control. It was the formal expression of the artist’s subconscious.

Borduas wanted to free himself of the norms, rules and preconceived notions imposed by society and thus allow his instinct to spring forth. He did not wish to represent an exterior, identifiable reality, but rather to express his feelings and perceptions. For Borduas, creative work was difficult. He sought ways to express the reality of sensations that belonged only in his interior, personal world. He was often dissatisfied with the result when he recognized the presence of details from the exterior world. Many times, when this happened, he would destroy a work and start over again. In his text, Projections libérantes (Liberating projections), Borduas described how difficult it was for him to create a completely satisfying painting:«Working in the studio is exhausting. After ten years of unrelenting labour, scarcely ten paintings are worth saving. I recognize them as happy accidents, impossible to repeat. The paintings that my will tries to direct with the most effort are those that become the most distant, the coldest, the most intolerable. I buy paint remover by the quart. Nonetheless, an almost unreasonable assurance encourages me to believe that someday work will be more transparent, less distressing.»

Borduas looked at his paintings with a very critical eye. He continuously cast doubt on his work, which led him to advance and go further in his pictorial exploration. Despite the many prejudices against abstract art, it requires much preparation and great rigour.

For Borduas, the challenge of abstract painting lay in the difficulty of expressing purely and sincerely that which dwelled in the subconscious, in other words, something that is not thought out. Expressing feelings or painting without a precise, previously determined subject allowed the artist to create forms, colours and lines with complete freedom. Borduas wanted to go further and liberate gesture and colour so that they would surge out to leave their trace on the canvas. This approach was also a way of freeing himself from the restrictions of tradition and the usual genres such as portraits and landscapes.

However, he saw all artistic production as part of a continuity rather than creating a true rupture. In Parlons un peu peinture (Let’s talk painting), he wrote:«Do not look for the mysterious key – it doesn’t exist. The door leading to the inner courtyard is wide open. Do not believe in closed art – all the roads of thought have led to it from the time of the Impressionists, for almost a century now. If it seems closed to you, it’s because you have not arrived there yet. If you haven’t yet arrived, it is probably because outdated sentimental values are snickering at you somewhere along the route. If so, plummet the depths of these values and try to exhaust their charm. Then you can continue on your way on the road leading to the present. No stage in the evolution of thought can be arbitrarily skipped.»

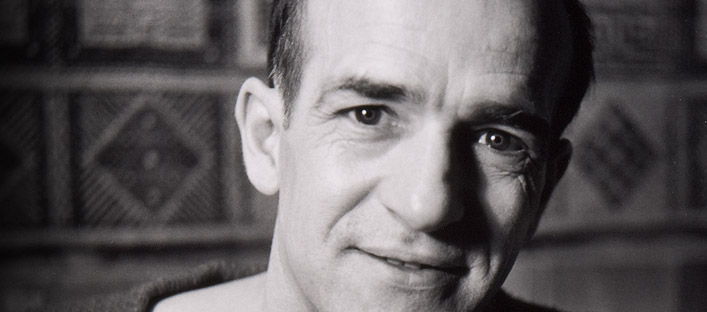

Header image: Portrait of Paul-Émile Borduas (detail).

Text by Robert Élie, “Borduas à la recherche du présent” (Borduas in search of the present), 1979:

«The succession of paintings, like an ascension in light, brings back memories of passionate conversations that continued ‘til dawn in the peace and joy of Saint-Hilaire’s gentle landscape.

A painting, the most recent one, would serve as an excuse for this hunt for words that would make it possible to explain the sense of poetic activity. Borduas … had to invent his own language.

He put as much passion and tenacity in this enterprise as he did in every other. Thus, everything he was taught by the language of form and colour is no less profound than that taught by the language of words.

This pursuit, which had taken him so far from the closed world of this youth, seemed enthralling to him simply because of the discoveries it promised.

The more he advanced in his quest – and the closer he got to the end of the adventure – the more the future looked luminous to him and the present moment like an absolute beginning. Finally, after a long period of patience, of severe asceticism, of indefatigable questioning under the most extreme physical and mental tension, Borduas emerged in such a vast, transparent space that the act of total liberty, a satisfying response to the most demanding passion for the absolute, was at last possible.

In the great interplay of the last paintings, the desire for high spiritual adventure begins to find fulfilment in this great interplay of black and white, of day and night, in which, however, shadow is as vivid as light.

Just as strength was deserting him, Borduas was certain that everything was just beginning, that work, once so distressing, had become a game in which one’s whole being exalted in every gesture, in which to live was to create and to create was to live and in which the correspondence between reality and his deepest desires, which he had never renounced, could be realized.»

© Musée des beaux-arts de Mont-Saint-Hilaire, 2014.

All rights reserved.