The artist becomes teacher

The transmission of knowledge

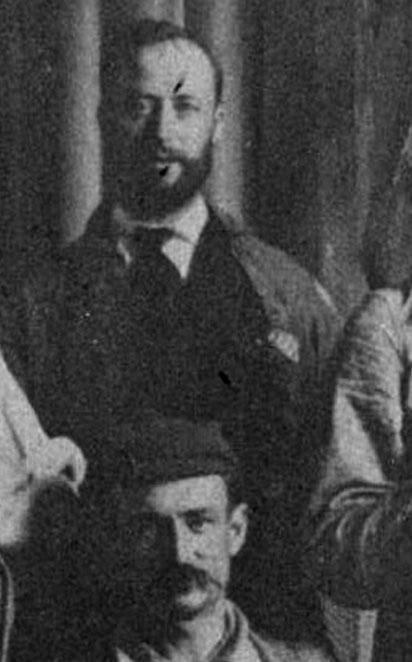

The years 1910 to 1920 are crucial in the career of Ozias Leduc as he starts receiving recognition from the general public as well as from the artistic and intellectual circles in which he is involved.

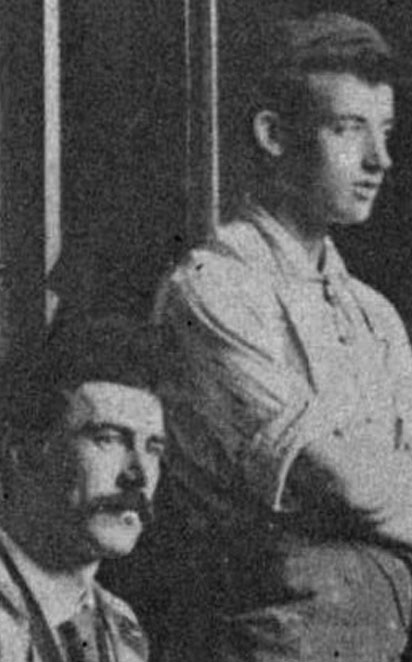

It's in this context that he meets 16-year-old Paul-Émile Borduas, in 1921. Also from Saint-Hilaire, the young artist is familiar with Leduc's work. Borduas shows him his drawings and watercolors. Leduc acknowledges the artist's talent and accepts him as an apprentice.

Ozias Leduc informally teaches Borduas basic artistic skills and encourages him in 1923 to perfect them at the Fine Arts School in Montreal. After graduating in 1927, Borduas is hired as a drawing teacher in a Montreal elementary school, then travels to France from 1928 to 1930.

Borduas develops non-academic teaching techniques based on his students' personalities. This nonconformism undoubtedly caused him to eventually lose his job. Following his return to Saint-Hilaire, and struggling to find work, Leduc helps Borduas in the early 1930s by hiring him as an assistant for the decoration of the churches of Lachine and Rougemont.

From the 1940s, Borduas turns to abstract and non-figurative painting. Despite artistic differences as early as the 1930s, the two continued to see one another and to respect their differences.

Leduc played an important role in Borduas' career. He writes:

I owe him a taste for beautiful paintings, even before I had met him. I also owe him the approval he gave me to pursue my destiny, one of the few I have received in my life (…) Finally, I owe him for allowing me to cross over from the Renaissance's spiritual and pictorial atmosphere to the future's power of dreams. - Paul-Émile Borduas

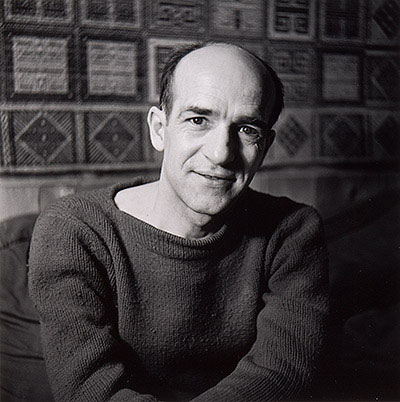

Paul-Émile Borduas

Paul-Émile Borduas writes about Ozias Leduc:

"I already knew his painting from this little church in Saint-Hilaire which he generously decorated and which is currently in danger of being sabotaged by clumsy repair work. From my birth to the age of about fifteen, these were the only paintings that I had seen. You wouldn't believe how proud I am of this unique source of pictorial poetry at a time of life when the slightest impression penetrates into the hollow of our selves and unwittingly orients the foundations of one's critical sense. How can we subsequently betray these directives, coming from who knows where, and that in our candor we are willing to attribute to destiny? It will probably seem strange for some people to hear that I have stuck with those first impressions. I believe it strongly, all the subsequent states of pictorial admirations must have agreed with them: believe it or not".